This piece by Dr Brett Glencross was published in the January 2023 edition of International Aquafeed magazine.

Everyone is seeking sustainability in food production systems around the world presently. However, to make effective decisions, and manage our various options you need to compare those options. This also means you need to measure things, which is commonly referred to as establishing “metrics”. This process of measuring and comparing things is a central part of the role of science in providing a basis for establishing relevant goals and measuring progress against them. In effect, you cannot manage something if you cannot measure it.

Sustainable choices in feed and food have led to the evolution of a range of metrics over the past forty years or more, however the format gaining most support over recent decades has been that of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). The LCA approach allows us to make sustainability choice management based on a comparison of the full range of environmental effects assignable to different products and services. It does this using a system that quantifies all the inputs and outputs associated with the various processes, material, and energy flows involved in producing a product or service. It then quantifies the associated environmental impactors that occur due to those flows. It has been described as something of an environmental accounting system, but it goes a long way beyond that.

Lifecycle assessment has a range of advantages in that it provides a framework for the development of a series of holistic sustainability metrics with traceability across the value chain. Arguably just as important is that it allows for greater cross sector harmonisation of metrics. For example, the variety of environmental impact categories that LCA examines can be equally applied to fishmeal, soybean meal and insect meal production systems, so that effective direct comparisons between each can be made. Within those impact categories, individual impact categories, such as global warming potential (a.k.a. carbon footprint), assessment can be applied to any feed ingredient, thereby underpinning the basis for the assessment of the full lifecycle impact of feed-production and allow the avoidance of trade-offs or cross-subsidisations of sectors through incomplete sustainability assessments.

Importantly, LCA is increasingly seen as the “mainstream” way to establish environmental credentials. Notably, the process of undertaking an LCA analysis though requires lots of planning and data, and how you plan and how you collect the data can have important effects on the interpretation. Because of these constraints, there have been various attempts to set some standards on this; the International Standardisation Organisation (ISO) initiated this (ISO 14040 series), but for the feed sector the EU have taken a lead with the establishment of the Product Environmental Footprint Categorisation Rules (PEFCR) approach. More recently the Global Feed Lifecyle-Assessment Institute (GFLI) was established to be an independent repository with freely available database and tools, that also provides overarching guidelines that all who input into the database need to follow.

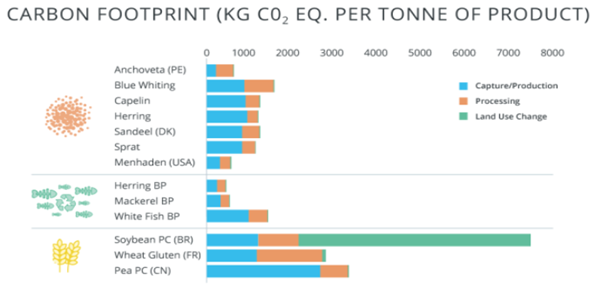

This whole issue of sustainability and carbon footprint was recently summarised in an excellent paper by Richard Newton and colleagues (Newton et al., 2022. Aquaculture, 739096), who compiled a summary of the lifecycle inventories of a wide range of marine ingredients. In that study, key alternative ingredients like soybean protein concentrate, wheat gluten and pea protein concentrate were also included (Figure 1), and when compared against various fishmeals, showed that the marine ingredients had very low environmental impacts in things like global warming potential (carbon footprint) and that there was significant variability among the various fishmeals that were assessed. It can further be seen from that study that marine ingredients across the board have very favourable environmental impact characteristics. So, another facet of what this study brings to light is a series of points on what constitutes a “sustainable” ingredient. The study shows that all ingredients have strengths and weaknesses, but arguably on balance it shows that the marine ingredients have a lower environmental impact than most, which could be argued as making them more sustainable than the alternatives.

Irrespective of what ingredient is actually more sustainable, there remains a growing demand for protein to underpin the growth of aquaculture. The growing reality is that it is not an either/or scenario, but rather we need more of everything. With a looming shortage of protein resources, the need for an approach with increasing circularity in resource use, may be what is required to fill that future gap. However, the challenge here remains as to how we can effectively implement these technologies at a scale to sustain the rate needed to provide those nutrients and to deliver this at a cost-point competitive in the marketplace based on their nutrient density. While there has been a boom in new initiatives promoting protein resources like insects, single-cell, and microalgae, among others. Notably the only circular ingredients with any scale (pardon the pun) have been the production of fishmeal and oil from trimmings and by-products. In 2021, this sector of the marine ingredients industry produced close to two million tonnes, around a third of total production, clearly putting it in a different league to the newer emerging “novel” ingredients sector. In fact, if we combine the existing low carbon aspects of marine ingredient production with the “circular” protein strategy we take something that has a pretty good environmental credentials already; low carbon footprint, low energy use, and little to no reliance land or freshwater, and make it into something super special, an ingredient with superb nutritional properties and an even lower carbon footprint (Figure 1).

By embracing an approach using a shared, and open metrics system, based on the LCA approach to assessing sustainability, the marine ingredient industry plans to ensure that they remain accountable on a more holistic and widely accepted path for environmental footprint assessment moving into the future. Additionally, through the growing role of by-product use and its ultra-low footprint, it is all certainly food-for-thought as to why the marine ingredients sector going forward is very much working on a basis of by measuring things better, being able to manage things better.

Figure 1. Carbon footprint (global Warming Potential) of a suite of forage and by-product fishmeals compared against other commonly used aquafeed ingredients. Data from Newton et al (2022).