This article, written by Dr Brett Glencross, was first published in the INFOFISH International, Issue 1/2022 (January/February 2023)

Where are we now?

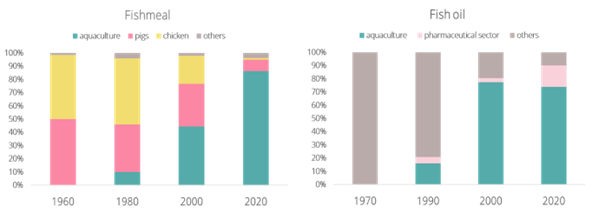

Marine ingredients, principally fishmeal and fish oil have been significant contributors to the animal feed industries for well over fifty years. Back in the 1960’s most of that production went to the pig and poultry sectors (Figure 1). Over time the emergence of aquaculture as a food production sector resulted in these ingredients being redirected to that more valuable (per unit weight) and feed efficient sector. In effect, an economic gravity was ensuring that the most valuable ingredients were being used by the most efficient sector. What we saw dropping out, in terms of use, was those sectors that could not justify the higher cost associated with the use of the ingredient. Now, in the 2020’s we see more than 80% of fishmeal being used by aquaculture, around 10% being used in piglet feeds, and the emergence of premium petfood as a sector as well. We see a similar trend emerging with fish oil, with increasing amounts being diverted from aquaculture towards the direct human consumption via the pharmaceutical sector (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Breakdown of global usage of fishmeal and fish oil by sector from 1960 to 2020. Source: IFFO 2022

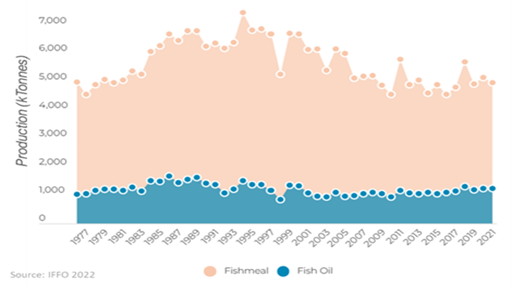

If we look at the production statistics of global fishmeal (Figure 2), we can clearly see over the period from 1980 to 2020, the volume produced stayed the same overall at about 5 million tonnes per annum. There was a temporary increase to around 7 million tonnes in the early 1990’s before the introduction of widespread fisheries management programs across most of the major fisheries resulted in stabilising volumes at around 5 million tonnes per annum from about 2005 onwards, where they largely have remained.

Figure 2. Global fishmeal and fish oil productional over the past fifty years. Source: IFFO 2022.

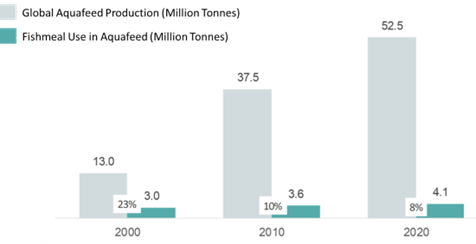

Over that period, with the growth of aquaculture over the past twenty years, the use of feed has grown from around 13 MTonnes in the year 2000 to the year 2020 when it used over 52 MTonnes (Figure 3). Notably, fishmeal use by aquaculture only increased from 3.0 MTonnes in 2000, to 4.1 MTonnes in 2020. This has meant that the proportional inclusion in aquaculture feeds has gone from 23% down to 8%. So clearly the biggest proportion (over 90% of it in fact) of aquafeeds in the present day is not marine ingredients, and the sector has learnt to use a much broader range of ingredients to sustain the growth of the industry. In the present day, marine ingredients are largely constrained to strategic use, where they are used to provide an important functional role in the feed sector.

Figure 3. Global production of aquaculture feed and usage of fishmeal in those feeds, shown as both volume and a proportion of total feed production. Source: IFFO 2022

Where are we heading?

Sustainability is increasingly seen by the marine ingredients sector as a non-negotiable condition as it underpins their long-term future. In this regard, it is important to note that most fisheries in developed nations of the world are now managed by independently set quota systems. Modern fishers are then regulated to operate within those quota systems. There has been a BIG shift in fisheries management of many parts of the world over the past 20 years. Recently published scientific studies have reported that when such effective fisheries management is implemented, there has been a clear improvement in fish stock status across multiple global fisheries, and notably those of the forage fishery sector.

What has been observed is that when small pelagic fisheries (anchoveta, sardine, herring, etc) are managed within their maximum sustainable yield (MSY), then they are sustaining their biomasses at expected levels. A reduction in fishing pressure has been central to that success, with widespread rationalisation of fishing fleets. In many cases, fisheries for small pelagics are arguably among the most sustainable of all fisheries, that many of them are large volume single-species fisheries has made that sustainability comparatively easier to achieve. However, there remains considerable room for improvement. Better management of trans-national stocks and quota sharing arrangements remain among some of the more intransigent issues to improve, with the most apparent blockages being political.

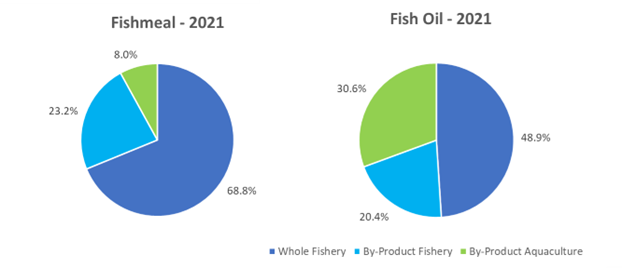

Another key direction of the marine ingredients industry is the new mantra of “no such thing as waste”, whereby there is increasing use of by-products and trimmings from both wild-catch and aquaculture fish resources (Figure 4). In fact, we can now see that over 30% of all fishmeal and more than 50% of all fish oil is now being obtained from by-products. Estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations predict that this trend will continue to grow. Given that only about 50% of most fish is edible meat, then it makes a lot of sense to valorise the remaining parts by converting them to useful nutrients that can retained within our food production systems, rather than going to landfill or incineration.

Figure 4. Global raw material origins of fishmeal and fish oil in 2021. Data from IFFO 2022

Sustainability is not a simplistic concept

In terms of marine ingredient use, or indeed any ingredient use for that matter, sustainable choices by the feed sector are growing in importance. Traditionally, metrics like Fish-In:Fish-Out (FIFO), and Forage-Fish-Dependency-ratio (FFDR) were the mainstay of the sustainability argument being presented against marine ingredients. However, over time it has become apparent that such simplistic metrics were not allowing the progression of a more meaningful discussion, which needs to be based on a shared metric system that allows the comparison of all ingredients being considered for a feed. Consequently, older metrics like FIFO and FFDR are being phased out and more holistic assessments like that posed by lifecycle assessment (LCA) methodologies are gaining favour.

Life Cycle Assessment aims to compare the full range of environmental effects assignable to products and services by quantifying all inputs and outputs associated with energy and material flows and assessing how these flows affect the environment. The process is based on compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and their associated environmental releases and then standardising all those releases to what we term “equivalents”, so that the environmental releases in any single impact category can be effectively compared against each other.

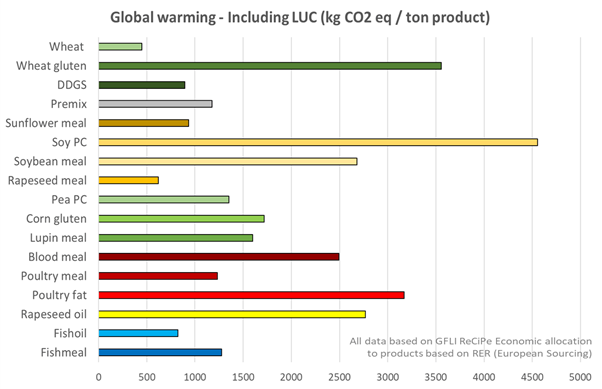

Increasingly LCA is being seen as the “mainstream” way to establish environmental credentials. However, the way in which an LCA study is undertaken (and reported), can have significant impacts on the outcomes. Because of this a range of standards have been established. Initially by the International Standardisation Organisation (ISO), and more recently by the European Union through their Product Environmental Footprint Categorisation Rules (PEFCR) process. Another recent initiative in this area, particularly relevant to the feed sector, has been the development of the Global Feed Lifecyle-Assessment Institute (GFLI), which hosts an independent database on close to 1000 ingredients. Each of those ingredients being included in the database using the same overarching data collection and reporting system, so that “apples-can be-compared-with apples” so to say. Among that database are about 60 marine ingredient data sets. Although the GFLI database has data on 19 different impact categories aligned with the LCA system, an examination of one of the impact categories, the Global Warming Potential (Carbon footprint), shows that marine ingredients compare very favourably when compared against an assortment of other ingredients typically used in farmed Atlantic salmon feeds (Figure 5). But arguably, what can also be noticed is that all ingredients have their strengths and weaknesses when considered on a sustainability perspective. Which is why it is important to move away from simplistic metrics to something more holistic and encompassing of all ingredients, so that a more informed decision can be made on sustainability.

Figure 5. A comparison of the data on global warming potential – including land use change (a.k.a. carbon-footprint) of various common ingredients used in farmed Atlantic salmon feeds around the world

Emerging opportunities

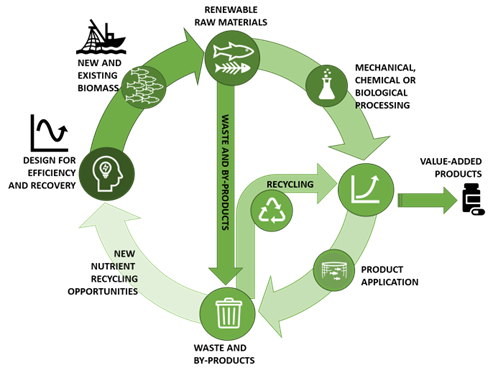

There are several emerging opportunities in the marine ingredients sector that are gaining momentum. One of those is that circularity is becoming increasingly important to the industry. Although most of the fish caught from the wild and farmed is for human consumption, generally less than 50% of that biomass is eaten. This means that there is a considerable amount of biomass available for repurposing. While much of this biomass used to be wasted, the valuable nutrients within are increasingly being valorised and there has been a growth in rethinking of supply-chains to consider circular thinking approaches (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Circular thinking is increasingly be adopted in the marine ingredients sector to valorise all parts of the fish on a “no such thing as waste” policy.

Another emerging opportunity has been that of fisheries that were once considered forage species which are now being redirected to food. This increasing consumption of fish resources lower in the food-chain is arguably a good move for sustainability, but importantly that trend to eat more fish like herring, mackerel and sardines still produces by-products, which end up as important raw materials underpinning marine ingredient production. By-products from aquaculture are also increasingly be used as the biomass in marine ingredients. With projected industry growth in aquaculture, there is a clear opportunity for future growth in the raw material base for marine ingredients.

Although there is growth potential in the fishmeal and fish oil part of the marine ingredients sector, largely through better use of by-products, with a (relatively) fixed resource base, increasing the value of the products through further product differentiation and production of specialist products is seen as another opportunity to generate additional value. Hydrolysates are one clear opportunity that has been recognised by the marine ingredients sector. These products are generally made by the enzymatic and/or chemical breakdown of protein-based raw material. Products can be produced with varying levels of free amino acids and short-chain peptides. While one key role for hydrolysates in the feed sector is for use as palatants to better manage the feed intake responses of animals, other products have also demonstrated immunological benefits. What we have also noticed is that different raw materials result in products with different properties. Other products from such value adding have been things like glucosamine and collagen products, which are finding markets in the pharmaceutical sector.

As we move towards the 2030’s the way forward for the marine ingredients sector is clearly one of consolidating sustainability and increasing their diversification. With the growing move towards valorising fish waste streams, the marine ingredients sector remains in a strong position to contribute to the future of the feed sector as a strategic player, whilst leaving other sectors to be the contributors of bulk nutrients.